Paramilitary Group Transition and the Sunk-Cost Fallacy

Why the process of 'conflict transformation' has failed to tackle paramilitarism

When I was in my late teens I spent the odd weekend evening in the “wee Blues club” in Rathcoole.

Every other Friday I’d watch a guy rest his pay packet on the top of the fruit machine, taking out a tenner at a time and exchanging it for pound coins at the bar.

He’d then play for most of the evening.

I could tell how he was doing by glancing over to the money he kept beside him in an empty pint glass.

Sometimes his luck was in and he received a pay out, which he would promptly feed back into the machine.

Most of the time his luck ran out.

Yet, he kept ploughing his money into the machine.

It was probably the first time I realised gambling was a recreational pursuit best avoided.

I remember the look of disappointment and annoyance on his face as he was forced to stop playing - his pay packet and pint glass now empty.

As he walked away there was always someone on hand to take over, including that one enterprising individual who would inevitably go on to win the jackpot!

What is the ‘Sunk-Cost Fallacy’?

In many ways, the guy who lost his weekly earnings found himself trapped in what behavioural scientists call the ‘sunk-cost fallacy’.

It’s a cognitive bias by which you continue an endeavour once an investment in money, effort, or time has been made. In one classic study psychologists found how those who had incurred a sunk cost were more likely to inflate their assessment of how likely a project was to succeed than those who had not (Arkes and Blumer, 1985).

When I think of the continuing facade of paramilitary ‘group transition’, I think of the guy in his work clothes, returning ever expectant to the gambling machine, week after week, content to throw his money away in anticipation of that one big “pay out!”

It was how I interpreted the comments of Lord John Alderdice who this week was quoted by BBC Northern Ireland as having said loyalist transition is “not working.”

“There comes a point when you have to say no, this hasn’t been delivered. It’s not going to be delivered. And, actually, by continuing we are making it worse. What I’ve seen is more talking about transition, and transformation, and no doubt with an invoice provided, for how much money is needed to be made available from public services in order to pay off these people” - Lord Alderdice, BBC News.

Inevitably a senior LCC source was quoted in the same reporting promising that “a final push for loyalist transition is imminent.”

On the face of it there is nothing wrong with the LCC taking such an upbeat view; interestingly it reflects a collective view of government bodies and statutory agencies who are united in shared hope of the one big pay off being just around the corner.

If only they keep throwing money at the problem it will eventually pay off.

This is the sunk-cost fallacy par excellence.

Preparing for Peace, Readying the Retirement Fund

Anyone holding their breath for an end of loyalist paramilitarism died of asphyxiation long ago.

Billions of pounds have been spent investing in the promise of ending paramilitarism and there is little to show for it other than the drop in the sectarian death rate caused by bombs and bullets.

In reality few acknowledge the indirect deaths that come as an inevitable by-product of the persistence of paramilitary structures.

In 1994 the UVF/RHC and UDA/UFF called a collective ceasefire, which led to a moratorium on killing Catholic civilians. It said little about the group’s intent towards the communities they lived in close proximity to, with both groups murdering dozens of Protestants over the next decade.

Although the Good Friday Agreement (1998) signalled a new departure, the paramilitaries stayed in place.

In fact, they simply grew in number.

Recruitment, illicit activities, paramilitary assaults and murders continued unabated.

Then in 2007 the UVF said it would put its weapons ‘beyond use’.

In 2009 the UVF and UDA finally signalled a more permanent end to their terror campaign.

Within months they were killing people who stood against them.

For the past 15 years they had become an even greater feature of the fabric of deprived and marginalised communities.

This is despite the British and Irish governments and Northern Ireland Executive pumping millions on pounds into what is known euphemistically as the “conflict transformation process.”

You might argue that this is akin to paying someone to give an undertaking not to burgle your house by entering the front door, while they go in through the back door and help themselves!

To place this in parlance now familiar in multiple Independent Reporting Commission publications, the leaderships of paramilitary groups do not “sanction” illicit activities but they cannot speak for their individual members. The moral cowardice is evident, as too is the cognitive dissonance necessary to keep up the facade.

Photo Ops for Peace

So why have we not seen the end of paramilitarism in Northern Ireland?

There are many reasons for the abject failure to tackle this insidious challenge.

Some veteran police officers I speak to in the course of my research tell me it’s because the community “must tolerate them.”

This sweeping generalisation does little to capture the complicated love-hate relationship between the community and paramilitaries.

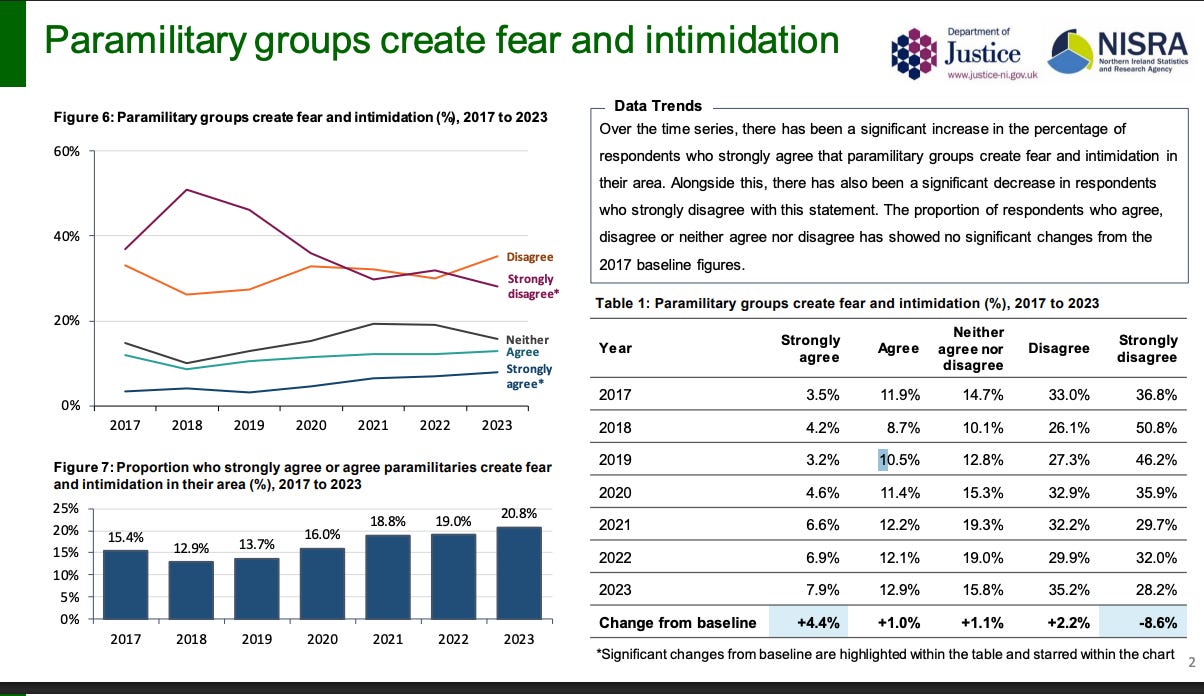

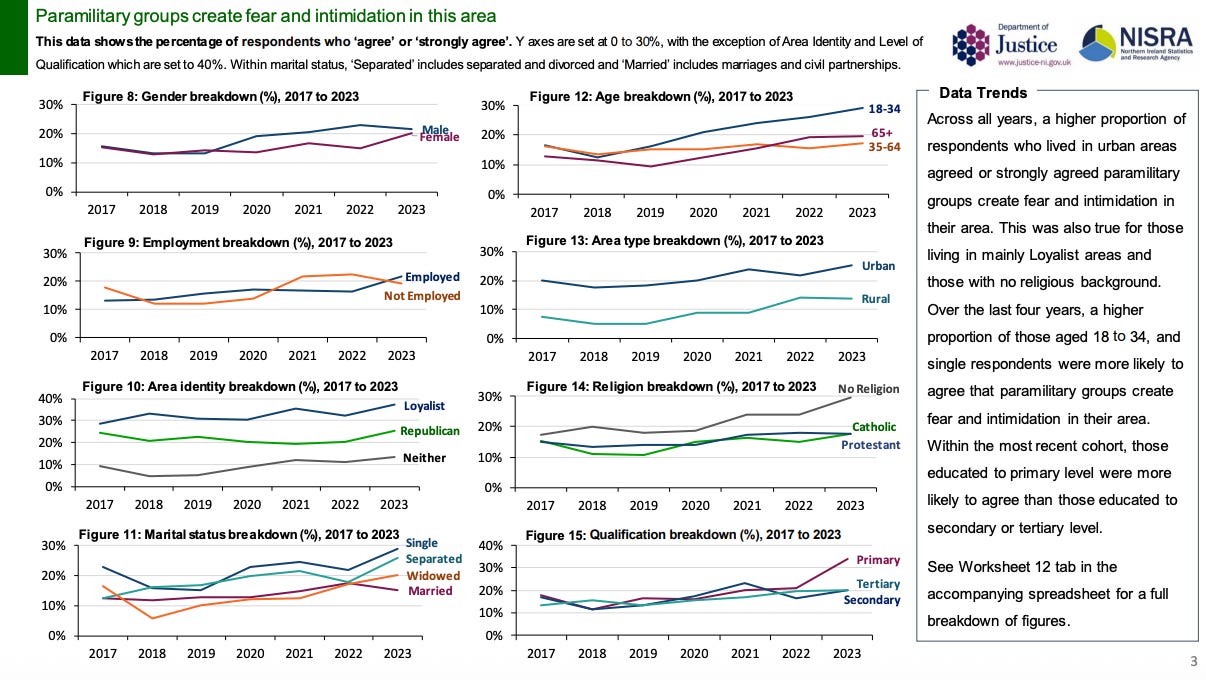

In fact, the Northern Ireland Life and Times survey data tells is that there has been a significant increase in the percentage of respondents who strongly agree that paramilitary groups create fear and intimidation.

What is also striking from this data is how consistent it is when those living in mainly Loyalist areas are surveyed.

I would further argue that paramilitaries are tolerated by all parts of society because well-meaning people, often living far beyond these areas, cling to the hope of the bigger windfall.

The problem with this cognitive bias is that it has become a deeply embedded logical fallacy.

It is unlikely to change without a revolution in mindsets throughout society.

I recall meeting a senior police officer some years back. I was introduced to him by a civil servant who announced I was the author of “a very good book on the UVF.” I was shocked when the officer in question asked me if I’d “spoken to… [such and such],” referring to one paramilitary leader by his nickname as if he was his squash partner!

You see, this is part of the problem with dislodging paramilitaries.

We have been told for decades that smiling photo ops demonstrate “how far we have come in Northern Ireland.”

I suppose it depends what people mean by that observation.

Do they mean temporally in terms of the 30 years since paramilitaries told us they were going away or the successive waypoints like 2007, 2009, 2015, etc, when they reiterated that view.

Or do they mean spatially in terms of the continuing separation of Protestants and Catholics who now live in a form of what Professor John Nagle and Dr Mary Alice Clancy call “Benign apartheid”?

Whatever route we have taken, a good proportion of people assume paramilitaries are on board the journey we are taking.

I am here to tell you, dear reader, from many years of professional experience, they are not.

Worse still, if you permit me another metaphor, they have never had any intention of riding off into the sunset.

Meanwhile, the great and the good fall over themselves to remain on first name terms with paramilitary leaders, even writing them references when they are caught ‘red-handed’ with a bag of guns in the boot of their car!

These ‘pillars of society’ persevere in their cognitive dissonance, while ordinary people are left with the stone cold reality.

Paramilitaries remain, and, worse still, it would appear sunlight has failed to act as an appropriate disinfectant in exposing their activities.

The Limits of State Power

In many ways all this reflects a more worrying trend, i.e. the failure of the state and its institutions to remove illegal armed groups from our midst, resulting in their de facto recognition as “interlocutors”, “stakeholders” or, worse still, “peacebuilders”.

This is not unusual, for there are plenty of examples worldwide, in the Middle East, South America and Sub-Saharan and North Africa, of paramilitary groups remaining in place years after internal armed conflicts end.

It speaks to the limits of state power and the reconfiguration of sovereignty.

I have sympathy with ordinary people who have lost faith in a system whose representatives are happy to pose for photo opportunities with the very same people they condemn.

It gives paramilitary groups a sense of agency, of stature, of, dare I say it, ‘legitimacy’.

It is deeply harmful to community safety.

Perhaps, as Lord Alderdice has said, we need a more coercive response - more stick and less carrot - to meet the insidious challenge these groups continue to pose.

For the reasons outlined above, this is unlikely to dislodge the logic of the sunk-cost fallacy underpinning the irrationality of paramilitary ‘group transition’ amidst a decades-long peace process.

Like that guy in the “wee Blues club,” standing patiently in his work overalls, nursing a long pint while observing his monthly pay packet vanish, the community await the ever-diminishing returns on their investments in the peace process.